On the Front Lines of Nuclear Safety

Jim Key’s blood ran cold a few years ago as he listened to a former worker at Chernobyl recount the explosion, fires and panic that swept through the power plant as the world’s worst nuclear disaster unfolded in April 1986.

The most wrenching part of the speaker’s conference presentation came when he saluted co-workers and first responders who fell sick and died in the weeks, months and years after exposure to the intensely radioactive environment.

The memory of that talk came flooding back to Key as Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine unleashed new risks at Chernobyl and underscored the heroic work of nuclear industry workers across the globe.

These workers normally operate behind the scenes in each country, outside the view of a public barely conscious of how much it relies on them to keep their communities safe.

That’s by design, explained Key, president of the United Steelworkers (USW) Atomic Energy Workers Council and former vice president at large of USW Local 8-550, noting the high level of confidentiality involved in the work.

“We just have always gone about it quietly. No fanfare, no ticker-tape parade,” he said, noting many of the USW members involved in this work have security clearances and cannot talk about their specific roles.

USW members at Paducah, Ky., and Portsmouth, Ohio, continue to decontaminate and decommission gaseous diffusion plants built in the 1950s to produce enriched uranium for the nation’s nuclear weapons program and power plants. Other USW members work on remediating the former plutonium production facility in Hanford, Wash., established during World War II as part of the Manhattan Project.

“These plants have provided a tremendous service to our nation, and the people who worked in them have been termed Cold War patriots,” explained Key, adding that USW members at these sites today still perform a dangerous duty breaking down contaminated plant components, shipping them out and undertaking many other kinds of clean-up work.

These workers—along with their USW siblings at other nuclear sites in Idaho, New Mexico and Tennessee—receive extensive training to detect radioactivity, operate sensitive equipment and ensure the integrity of work sites while keeping themselves as safe as possible. The USW’s Tony Mazzocchi Center even volunteered to train a new generation of radiation control technicians who work on the front lines of safety at sites like Paducah and Portsmouth.

It’s this laser focus on security and safety that Key sees eroding at Ukrainian nuclear sites, despite the herculean efforts of his counterparts there.

Russian forces attacked Zaporizhzhia—the largest nuclear power plant in Europe, capable of producing a disaster the magnitude of “six Chernobyls”—and started a fire that Ukrainian firefighters had difficulty containing because of the shelling. Video footage shows workers yelling over a loudspeaker for the Russians to stop firing, with one warning, “You are endangering the safety of the entire world.”

Putin’s army also attacked Chernobyl last month at the start of the invasion, and Russian forces in recent days twice interrupted a power supply needed to ensure the plant’s safety.

Now, after occupying the facilities, Russian commanders want to tell highly trained power plant workers how to do their jobs. That’s a violation of international safety protocols intended to ensure the professional operation of nuclear sites and protect workers from duress.

“They have no nuclear reactor operating knowledge or experience,” Key said of the Russian soldiers, noting security at nuclear facilities around the world is intended not only to preserve countries’ secrets but to keep potentially lethal material away from people who aren’t trained to handle it.

Worse, Russian soldiers are treating nuclear workers as hostages, forcing them to work virtually around the clock at gunpoint while restricting their access to medicine and contact with the outside world.

Key praised the Ukrainian workers’ skill and fortitude. But sleep deprivation and other stressors increase the risk of catastrophe, he said, noting employers of USW atomic workers must follow strict scheduling rules intended to prevent worker fatigue and the hazards associated with it.

The world’s nuclear professionals work across international boundaries to learn from each other, enhancing their safety and that of all they serve.

Key traveled to Turkey a few years ago for one such collaboration—the international conference that brought in the former Chernobyl worker as a guest speaker.

It angers him that Putin’s aggression threatens the nuclear safety that he and others across the world spent lifetimes building. And he worries about a new wave of Ukrainian workers dying at Chernobyl.

“I can’t imagine how stressful it is for them right now,” Key said. “The human body and mind can only take so much.”

*

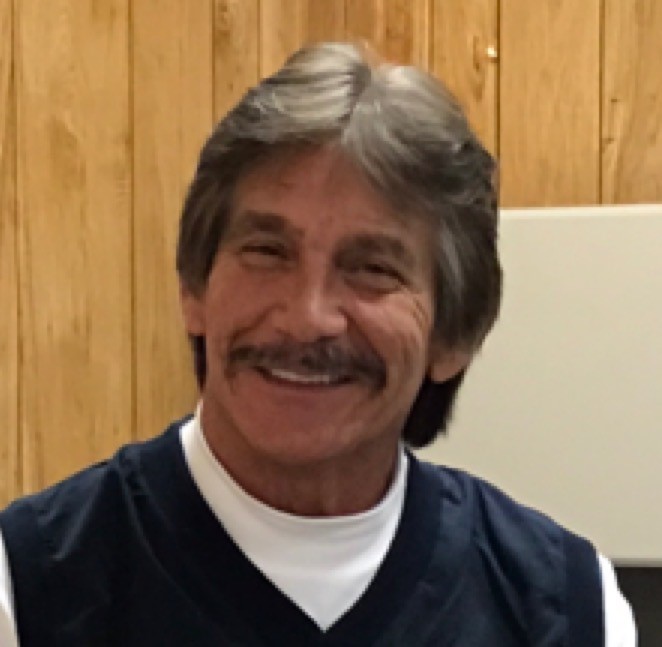

Photo of Jim Key

By clicking Sign Up you're confirming that you agree with our Terms and Conditions.

Related Blogs

Ready to make a difference?

Are you and your coworkers ready to negotiate together for bigger paychecks, stronger benefits and better lives?