Making Worker Power A Constitutional Right

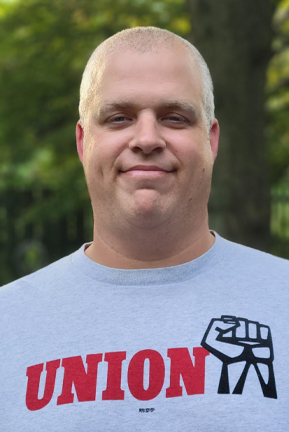

Chris Frydenger’s young co-workers at the Mueller Co. performed the same work and brought the same dedication to their jobs as he did, but the manufacturer’s two-tier wage system exploited newer hires by paying them thousands less each year.

Outraged by the unfairness, Frydenger and the entire membership of United Steelworkers (USW) Local 7-838 in Decatur, Ill., took a stand during contract negotiations a few years ago and not only beat back the inequitable pay system but won younger members catch-up raises of more than 21 percent.

That collective victory remains one of the proudest moments in Frydenger’s life. And now it’s fueling his fight to make worker power a constitutional right in his home state.

A Nov. 8 referendum will give Illinois voters the opportunity to enact a “Workers’ Rights Amendment” to the state constitution, enshrining in the state’s highest law Illinoisans’ freedom to join unions and bargain collectively for better lives while also barring future legislation that would erode worker strength.

The ballot question passed the Legislature on a bipartisan basis last year, a sign of how much the measure reflects the people’s will. As they educate more voters about the referendum, Frydenger and other activists find almost unanimous support for a measure that would give workers greater control of their destinies, beyond the clutches of CEOs, pro-corporate politicians and other anti-labor forces.

“I can’t imagine why anybody wouldn’t be in support of this,” said Frydenger, grievance chair and Rapid Response coordinator for Local 7-838, who’s canvassing neighborhoods, distributing leaflets and making phone calls to make sure workers know that their very futures are on the ballot this year.

The Workers’ Rights Amendment would help future generations negotiate the family-supporting wages needed to sustain the middle class and the nation’s economy. It would safeguard Illinoisans’ right to a voice on the job, including the freedom to call out unsafe working conditions without fear of reprisal.

And it would ensure workers can band together, as Frydenger and his colleagues did, to hold employers accountable. Frydenger recalled the local’s negotiating committee tossing a pile of worker surveys on the bargaining table—all demanding elimination of the two-tier wage system—and telling management there’s no way union members would ever vote for a contract that retained it.

The constitutional amendment has deep emotional meaning to Frydenger, who observed that it would confer “sacred,” “fundamental” and “essential” status on workers’ rights at a time that more and more Americans view union membership as the path forward.

“Every time I turn on the news, I see an Amazon location or another Starbucks store voting in a union,” he said, noting a new Gallup poll this week showed that 71 percent of Americans support organized labor, the most since 1965.

“I think the pandemic showed people that their employers didn’t care about them as much as they thought they did,” Frydenger said. “It’s up to us to secure our rights in the workplace.”

Even in Illinois, a strong union state, workers must remain on guard against efforts to rig the scales against them. Just a few years ago, a pro-corporate, anti-union governor proposed so-called “right-to-work zones” where organized labor would have been forced to represent workers regardless of whether they actually joined unions, a scheme intended to divide workers and undermine their collective power.

“In an era when corporate-bought politicians and lobbyists are doing everything in their power to undercut workers’ rights, this would really help us level the playing field,” explained Aaron Sutter, incoming vice president of USW Local 4294, which represents hundreds of members at Cerro Flow Products in Sauget, Ill.

Sutter, raised by a postal worker and a public-school teacher, grew up knowing that union wages “kept my household running and fed me every night.”

But not until he took a job at a nonunion package delivery company with abusive managers and shoddy equipment did he fully understand the role unions play in protecting workers and helping them obtain their fair share. He vowed never to work in a nonunion shop again.

“We’re living at a time when a pizza party is the most appreciation you can get without collective bargaining,” observed Sutter, who’s going door-to-door to educate voters about the amendment.

The referendum requires a supermajority of votes for passage, but that also means anti-union forces would face an uphill battle if they ever tried to alter or repeal it. An attempted rollback would almost certainly be doomed to fail, Sutter said, predicting voters will guard it as zealously as Social Security and Medicare.

Cathaline Carter, a retired union school teacher and member of the Steelworkers Organization of Active Retirees in Chicago, feels juar that strongly about the amendment because of what organized labor has done for generations of her family—and what it has the potential to do for generations more.

Carter’s uncle, Robert Jenkins, left rural Mississippi in the 1940s with little more than the shirt on his back and found his way to Chicago, where he took a union job at Youngstown Sheet and Tube. He worked his way up to crane operator, earning good wages that enabled him to buy a house, start a family and break into the middle class.

Union contracts also gave him the resources to help to relocate other family members, including Carter’s mother, to Chicago. Carter and other members of the extended family then followed in Jenkins’ footsteps, lifting themselves up with union work of their own and building on the progress he made.

“It gave him status in life,” she said of Jenkins’ union job. “He had things that people are struggling to have now.”

*

Photos of Chris Frydenger and Aaron Sutter

By clicking Sign Up you're confirming that you agree with our Terms and Conditions.

Related Blogs

Ready to make a difference?

Are you and your coworkers ready to negotiate together for bigger paychecks, stronger benefits and better lives?