Bringing Workers Sensibility to Local Government

When a group of custodians in York County, South Carolina, learned their bosses planned to sell them out to save a few pennies, they knew exactly who to turn to for help—a fellow worker who’d walked in the very same shoes.

County Councilman William “Bump” Roddey, a longtime member of the United Steelworkers (USW) and a former custodian himself, assured the county workers that he had their backs. Roddey ultimately helped quash the scheme to contract out the county’s janitorial services, a victory both for the custodians and the taxpayers relying on their quality work.

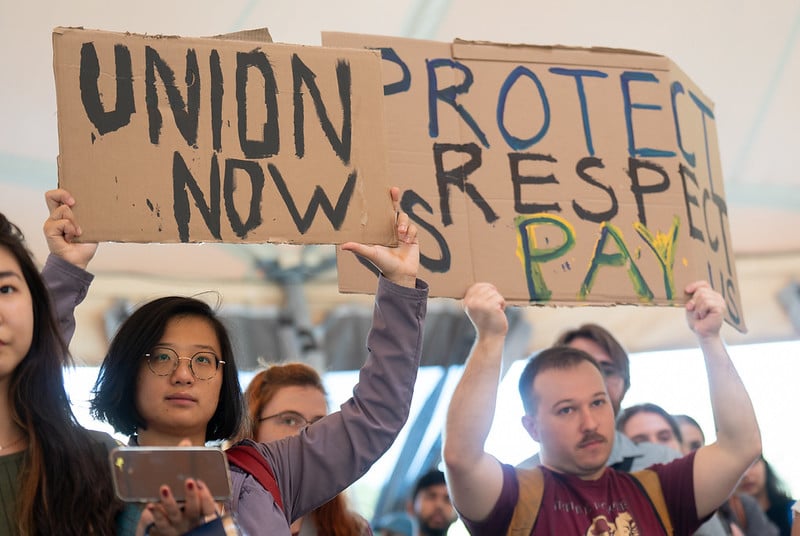

Electing more union members like Roddey to councils and mayoral posts will help to combat right-wing attacks on workers and hold local government accountable to the ordinary people it’s intended to serve.

“We speak for the American worker,” Roddey, a member of USW Local 1924 who works at New-Indy Containerboard, said of union members. “We speak for the middle class. The agenda is not about us if we are not at the table.”

If the county had privatized cleaning services, any small budgetary savings would have paled next to the pain inflicted on the custodians, Roddey said, noting officials out of touch with working people “don’t too quickly grasp these scenarios.”

“The perspective of the people who sign the front of the paycheck is different from the perspective of the people who sign the back of the paycheck,” said Roddey, whose colleagues on the council include three business owners. “I bring that back-of-the-paycheck perspective to everything I do.”

Attacks on working people aren’t unique to South Carolina.

After the school board in Putnam, Conn., contracted out custodial services, for example, workers lost access to their pension system even though they’d been promised no change in benefits.

In recent months, USW-represented school bus drivers in Bay City, Mich., beat back efforts to contract out their work, while union members in Los Angeles County, California, won their own fight against privatization.

Electing more union members would ensure that local officials instead invest their energies in productive ways, such as building robust, worker-centered economies.

Some forward-thinking local officials have used their authority to pass worker protection laws, to establish agencies for enforcing those safeguards and to create workers councils to take testimony on job-related issues, noted the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), a Washington, D.C.-based thinktank, in a recent report. At Seattle’s Office of Labor Standards, for example, a full-time equivalent staff of 34 enforces 18 worker-centered ordinances, including those requiring paid sick time, employment opportunity and protections for gig workers.

Local officials have the power to hold corporations accountable when they accept public subsidies with promises of creating dignified, family-sustaining jobs. It’s also the prerogative of mayors and councils to provide resources, like affordable housing, that help level the playing field for struggling workers.

And the advocacy of local officials can buoy workers in difficult times. Roddey and other leaders stepped up to support workers at Giti Tire in Chester County, South Carolina, during a USW organizing drive sparked by low pay, unsafe working conditions and discrimination.

“I certainly recognize the challenges that workers are facing every day at Giti,” said Roddey, part of a community coalition that signed a letter to corporate management last November demanding an end to its abusive practices.

Having union members in charge at city hall not only protects jobs but may even help to ensure the survival of the community itself.

Clairton, Pa., Mayor Richard Lattanzi points out that no one can adequately represent his city without a deep appreciation for the Clairton Coke Works and the Steelworkers who have anchored the community for decades.

And while meeting the daily needs of his constituents, many of them USW members and other union workers, Lattanzi also must defend the coke works against extremists eager to shut it down. “That’s one-third of our tax base, and that’s our identity,” said Lattanzi, a longtime USW member who worked at the Irvin Works in the nearby community of West Mifflin.

Some union members run for local office because their concern for co-workers spills over into the communities they call home.

“Our job as a union and as union leaders is to take care of people, especially working people, and that’s what our communities are made up of,” observed Steve Kramer, president of USW Local 9777 and a member of the Dyer, Ind., Town Council, calling his step into government service “a natural and easy progression.”

Union membership equips workers with the skills they need for public office. Union members understand the power of solidarity and diversity. They’re accustomed to having a voice and standing up for what’s right.

“What better person to run for elected office than a union member? We’re problem-solvers,” said Kramer, who’s helped to ensure that Dyer buys American-made products, that town-funded projects support good jobs and that government resources are equitably distributed across the community.

“I wish more union members would step up and do it. I know we have talent out there,” he continued, noting that in addition to elected positions, communities need volunteers to serve on water, library and many other boards.

An influx of union members into councils and other local posts would also help pave the way to more worker representation at other levels of government. As these local officials move up to higher office, Roddey noted, state legislatures and Congress will become more responsive to the will of the people.

“There’s a path to changing how these bodies operate, and the first step is getting involved locally,” he said.

By clicking Sign Up you're confirming that you agree with our Terms and Conditions.

Related Blogs

Ready to make a difference?

Are you and your coworkers ready to negotiate together for bigger paychecks, stronger benefits and better lives?