Protecting the Caregivers

The patient intended to commit suicide and knew the worker making his bed at Essentia Health-St. Mary’s Medical Center in Duluth, Minn., stood in the way.

So he crept up behind the caregiver, grabbed the cord to the call bell and began choking her with it.

Only chance saved her, recalled Tuan Vu, a longtime hospital worker who was on duty in another part of the facility that day, noting the woman’s colleagues rushed to the rescue after the struggle inadvertently activated the call bell.

The U.S. House just passed a bipartisan bill, the Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act, to curtail the rising epidemic of assaults on doctors, nurses, certified nursing assistants, case managers and others on the front lines of care.

The legislation, now before the Senate, requires hospitals, clinics, medical office buildings and other facilities to develop violence-prevention plans that cover the unique needs of each workplace.

For example, Vu said, a plan requiring that only specially trained behavioral health workers care for suicidal patients would have been one possible way to avert the near-strangulation of his co-worker a few years ago. She was assigned to the patient’s room that day even though she wasn’t a mental health specialist.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) would enforce the violence-prevention act and intervene if workers experience retaliation for reporting safety lapses.

“Having this type of legislation would put our safety at the forefront,” explained Vu, a behavioral health technician at Essentia and unit president of United Steelworkers (USW) Local 9460, which represents thousands of workers at more than a dozen northern Minnesota medical facilities. “It’s not something people should be desensitized to.”

“I’m a big guy. I’m not so worried about myself,” said Vu, who’s had racial epithets hurled at him and endured bites, kicks, punches and inappropriate touches over the years. “But I worry about some of my co-workers.”

Health care professionals are five times more likely to encounter violence on the job than other Americans. The crisis has festered for years. Workers face assaults from patients with substance abuse, dementia or cognitive issues, and they’re attacked by patients’ stressed-out family members.

The COVID-19 pandemic made a horrific situation worse. Even as they grappled with staffing shortages and infection-control protocols, workers experienced a spike in assaults from patients and others upset with mask requirements, restrictions on visitors and financial pressures stemming from the coronavirus.

No one is safe. When a patient attacks a health care worker, the struggle can spill into hallways, nearby treatment rooms or parking lots, putting other patients and visitors at risk.

At the urging of the USW and other unions representing caregivers, the House initially passed the violence-prevention bill in 2019. USW members and retirees alone collected 80,000 signatures demanding enactment of the legislation.

But the Republicans then in control of the Senate refused to consider the measure. Now, as injuries continue to mount, it’s more critical than ever to get the bill through the Senate.

Right now, OSHA recommends health care facilities adopt violence-prevention plans. But the agency doesn’t require them. Many medical facilities pinch pennies on security and look the other way when workers experience violence on the job.

“Something needs to change,” insisted Jessica Johns, a senior technician at Cleveland Clinic Akron General in Ohio who estimated she’s been assaulted 100 times in the past 10 years.

“I’ve been hit. I’ve been scratched. I’ve been spit on. I’ve been bitten. I’ve got dents in my legs from people kicking me,” said Johns, whose role as a “floater” requires her to work in whatever part of the hospital needs her that day. “I just can’t believe the violence happens as often as it does.”

A few weeks ago, Johns faced one of her biggest scares yet. A patient grabbed her by the hair and pulled her down onto the bed. She thrashed furiously to get away and injured a knee while kicking against the bed frame.

But she felt even worse when a patient recently scratched a colleague and left a permanent injury. “Now, she has a scar on her face,” said Johns, who represents hospital workers as a member of the USW Local 1014L executive board.

Instead of going the extra mile for safety, employers often expect health care workers to accept violence as a part of the job. They trivialize incidents or try to portray them as the staff members’ fault.

That’s reprehensible, especially when so many attacks can be predicted and avoided. The violence-prevention bill requires medical facilities and social service agencies to identify safety weaknesses and take a proactive approach.

For example, enclosing nurses’ stations, installing panic buttons and using heavy, hard-to-move furniture are all common-sense measures affording greater protection. Johns, lightly stabbed with a butter knife on one occasion, wonders why any facility still serves meals with metal silverware.

Assigning behavioral-health specialists to care for suicidal or aggressive patients is one idea for reducing assaults. Providing a basic level of mental health training to all of a facility’s workers, Johns said, is another safeguard.

Workers also would like to see facilities install more metal detectors, hire sufficient numbers of security guards and maintain staff ratios that ensure all patients receive proper attention. And employers need to show they have workers’ backs when assaults occur.

Vu said he and his colleagues have run out of patience with employers willing to let them return home bruised and bloodied at the end of their shifts.

Not only do facilities need to implement violence prevention-plans with all due speed, he said, but front-line workers earned a role in formulating them.

“We’re the ones that are out here,” Vu said.

*

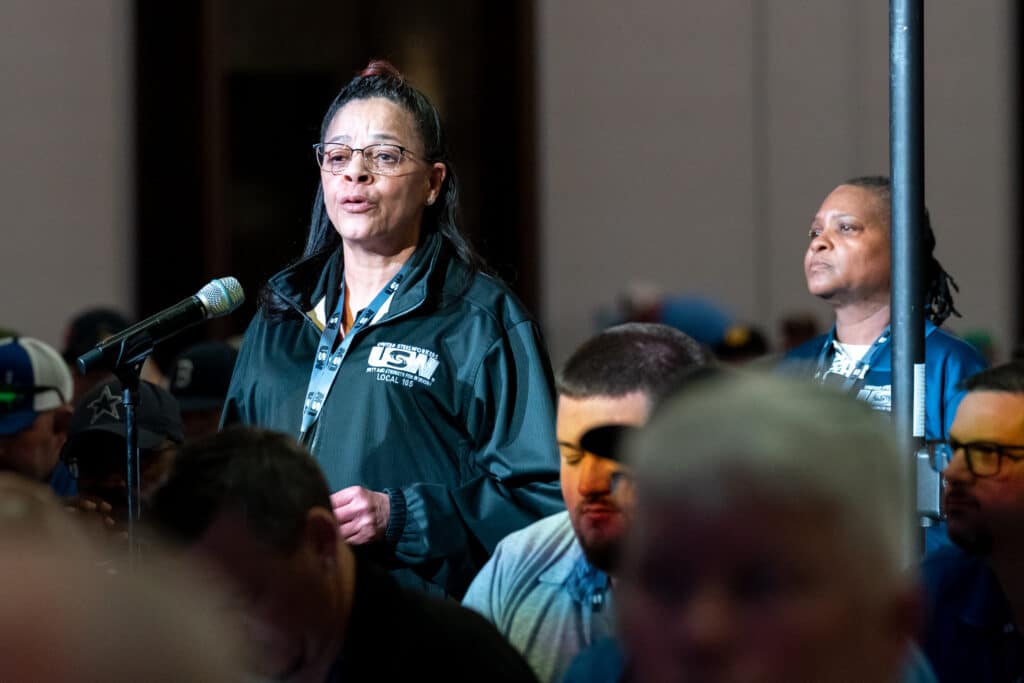

Photo of Jessica Johns

By clicking Sign Up you're confirming that you agree with our Terms and Conditions.

Related Blogs

Ready to make a difference?

Are you and your coworkers ready to negotiate together for bigger paychecks, stronger benefits and better lives?