Ending the Race to the Bottom

Chris Reisinger and his co-workers recently added a third daily shift at the Metal Technologies Inc. (MTI) Northern Foundry because surging vehicle sales boosted demand for the tow hooks, steering components and other auto parts they produce.

Yet Reisinger knows that jobs at the Hibbing, Minn., facility will always hang by a thread—even in really good times—as long as his employer has the option to shift production to poorly paid Mexican workers.

Americans can protect their own livelihoods by ensuring their Mexican counterparts have unfettered, unconditional use of new labor reforms intended to lift them out of poverty and stop employers from exploiting them.

To protect workers on both sides of the border, America’s labor community and the U.S. trade representative last week filed the first-ever complaints under the 10-month-old United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), demanding action against two plants that suppressed Mexican workers’ right to unionize.

Swift, significant punishment of these kinds of offenses through the USMCA’s innovative “rapid response” enforcement procedures would deliver a major boost to Mexican workers’ efforts to form real unions for the first time. And those unions, in turn, would help Mexican workers negotiate better wages, eliminate employers’ incentive to move jobs out of the U.S. and end a corporate race to the bottom that’s harmed millions in both countries.

Not only has Reisinger seen a steady stream of U.S. automakers and suppliers send work to Mexico over the years, but his own employer opened a location there about three years ago. Reisinger, who represents about 50 Northern Foundry workers as president of United Steelworkers (USW) Local 21B, doesn’t want to see the company open a second just to take further advantage of low wages there.

He’s counting on the USMCA to help keep that from happening.

“It’s just frustrating to see work going away from American workers,” said Reisinger, noting MTI could have expanded the Northern Foundry or its other U.S. locations rather than open the Mexico facility.

Under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the previous trade deal in place for 25 years, U.S. corporations relocated about a million good-paying manufacturing jobs south of the border to exploit the abysmal wages, weak labor laws and lack of environmental safeguards.

These companies made huge profits at the expense of powerless Mexican workers while devastating U.S. manufacturing communities, gutting the nation’s industrial capacity and decimating the middle class.

To curb this greed, U.S. labor leaders and their Democratic supporters in Congress successfully battled to enshrine tougher labor standards in the USMCA as well as enforcement mechanisms to hold employers’ feet to the fire.

The USMCA, for example, required Mexico to pass laws enabling workers to form democratic unions, select their leaders and negotiate real contracts for the first time.

Those changes empower Mexican workers to kick out the corrupt cabals—masquerading as labor organizations—that for decades collaborated with employers to suppress wages, stifle dissent and even kill those who publicly challenged the status quo. These groups not only denied workers a say on the job but bound them to oppressive contracts that made them the perfect targets for U.S. corporations preying on cheap labor.

Now, Mexican workers can look forward to joining unions that, like Reisinger’s, fight not only for better wages but affordable health insurance, retirement plans and safety measures to ensure they return home safely to their families at shift’s end.

“It gives you a voice,” Reisinger said of the local he’s proud to lead. “We have pushed back against the company several times on safety issues.”

Eradicating the anti-worker forces entrenched in virtually every Mexican workplace would have been a herculean, time-consuming process even without delays associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

In December, the Independent Mexico Labor Expert Board, created to monitor the labor reforms, noted that progress had been made with the help of well-intentioned Mexican officials.

However, the board reported that “serious concerns” remained. Most workers still awaited opportunities to form unions and elect leaders, for example, and many continued to face intimidation for organizing efforts.

Those are some of the issues at the heart of the complaints filed last week.

The AFL-CIO, other unions and the activist group Public Citizen alleged that Tridonex, an auto parts maker owned by a Philadelphia company, harassed and fired hundreds of workers trying to organize. Hourly wages at Tridonex range from about $1.80 to $3.30.

In a separate complaint, the U.S. trade representative reported that a phony labor group trying to cling to power at a General Motors plant in northern Mexico destroyed the ballots of workers seeking legitimate representation for the first time. Workers in the GM factory, which makes Chevrolet Silverado and GMC Sierra trucks, start at $1.35 an hour, with a top wage of $4.95 an hour.

Now, these employers face investigations by the Mexican government, special panels set up under the USMCA or both. Punishments for individual plants found to have violated the new labor rights include tariffs or other sanctions, and repeat violators could have their products denied entry to the U.S.

Strict enforcement of the USMCA will not only help the oppressed workers at the Tridonex and GM plants but send the message to other employers that they have to comply with the law as well.

“Otherwise, they’re just going to laugh at it,” Reisinger said. “You have to have these enforcement mechanisms in place, and you have to utilize them.”

Noting his foundry has struggled at times, Reisinger knows a more level playing field under the USMCA can help secure the facility’s future, generate even more business and help his co-workers build better lives.

“I think it’s important that they remember to share that increase with the workers,” he said.

*

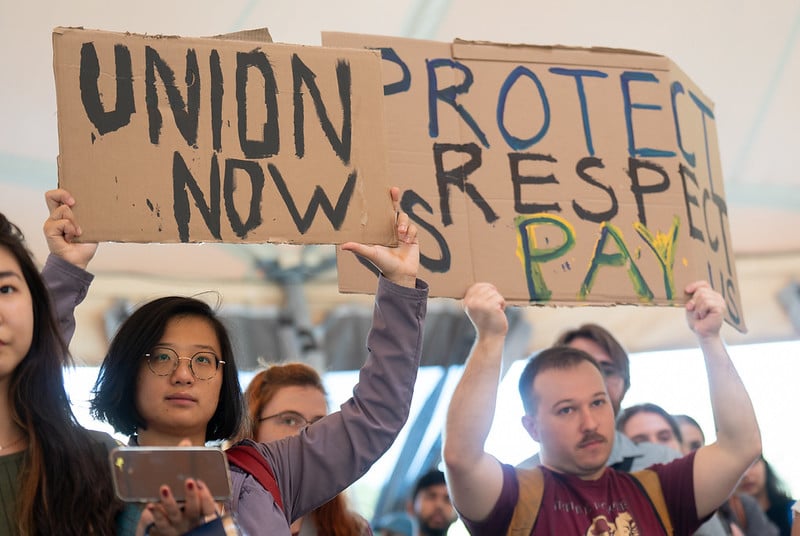

Photo of Chris Reisinger

By clicking Sign Up you're confirming that you agree with our Terms and Conditions.

Related Blogs

Ready to make a difference?

Are you and your coworkers ready to negotiate together for bigger paychecks, stronger benefits and better lives?